Following the introduction of LiDAR on iPhone, Meta wanted to understand whether and how people might bring their physical spaces into the Metaverse.

Bringing Physical Space into the Metaverse

When Apple introduced LiDAR to the iPhone, Meta wanted to understand whether this new capability could meaningfully enhance Metaverse experiences. Rather than starting with a product to build, the goal of this project was exploratory.

We set out to answer three fundamental questions:

- Why would someone want to bring their physical space into the Metaverse?

- What technical capabilities would be required to enable this?

- What might the user experience look like for any future product?

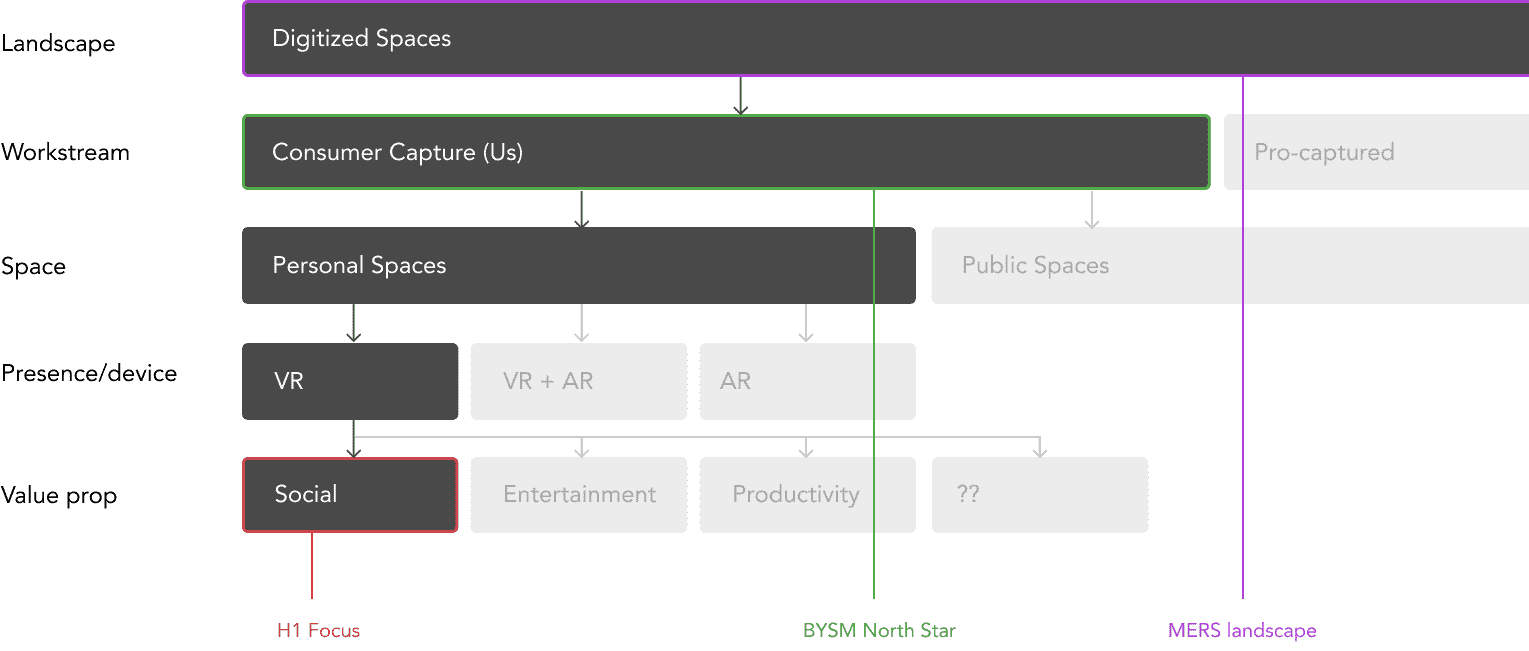

Establishing Direction in an Undefined Space

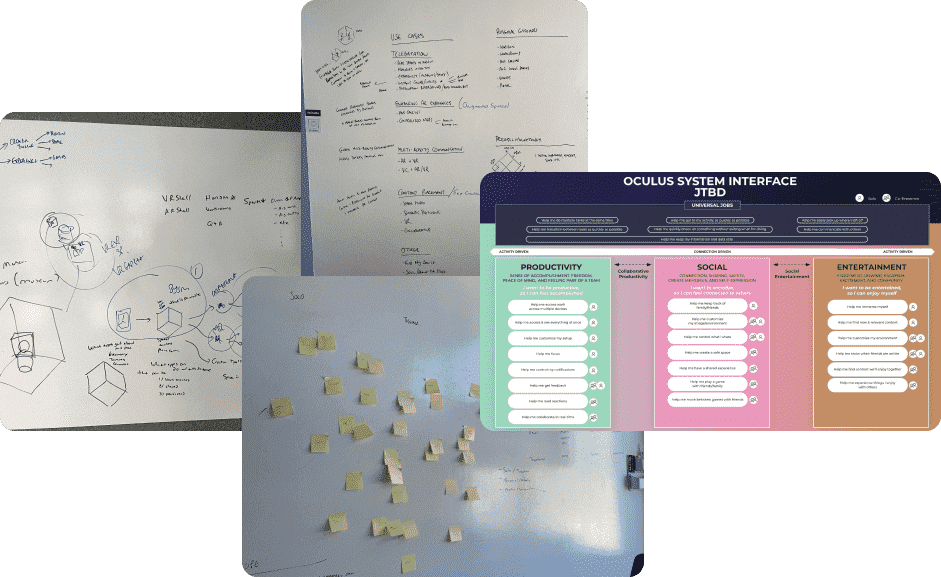

Given the novelty of the problem, there was little existing research to draw from. I began by running a design sprint with stakeholders across design, research, and engineering to surface current assumptions and unknowns.

This created a shared baseline that allowed engineering teams to explore technical feasibility in parallel, while we focused on identifying and evaluating potential use cases.

Early exploration surfaced many possible directions, but most led to vague or unfocused outcomes. To progress, we needed a clear primary use case. Using internal interviews and literature reviews of related research, we validated and refined our concepts.

Through this process, social connection emerged as the strongest and most coherent driver. This decision clarified our goals and helped adjacent teams understand how their work intersected with ours.

Defining Capture Requirements

With leadership alignment on direction, we shifted focus to understanding what users would need from the process of digitizing their space.

Three core requirements consistently surfaced:

- Privacy: Retaining granular control over what is and isn’t shared.

- Personalization: Allowing customization while preserving physical layout.

- Effort: Minimizing time and friction during capture.

Initial assumptions centered on capturing a single photogrammetric mesh of an entire space. However, when evaluated against these requirements, this approach proved problematic—high capture time, heavy data payloads, limited privacy control, and constrained personalization.

Rather than pivoting to fit the technology, we aligned with leadership to stay focused on the user experience and redefine what capture needed to be.

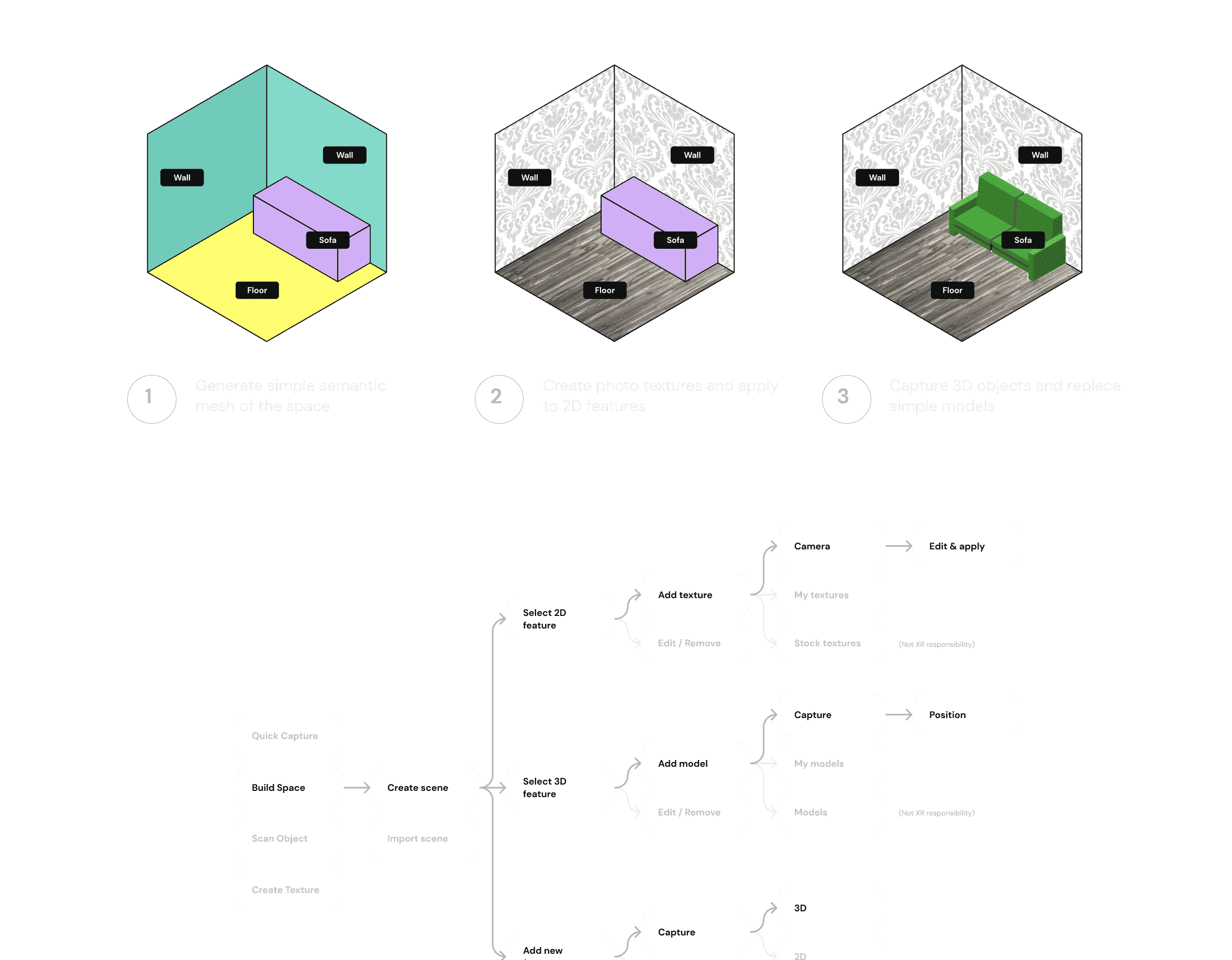

Redefining Capture and the User Experience

Working closely with engineering, we defined an alternative approach using semantic recognition to capture spaces as collections of individual surfaces and objects, rather than a single mesh.

This enabled a lighter-weight, extensible representation of space with object-level privacy and editing, and supported multiple modes of representation:

- Lifelike: Generated directly from captured textures and meshes.

- Stylized: Clean reconstructions using realistic stock assets.

- Customized: Artistically modified spaces that retain real-world layout.

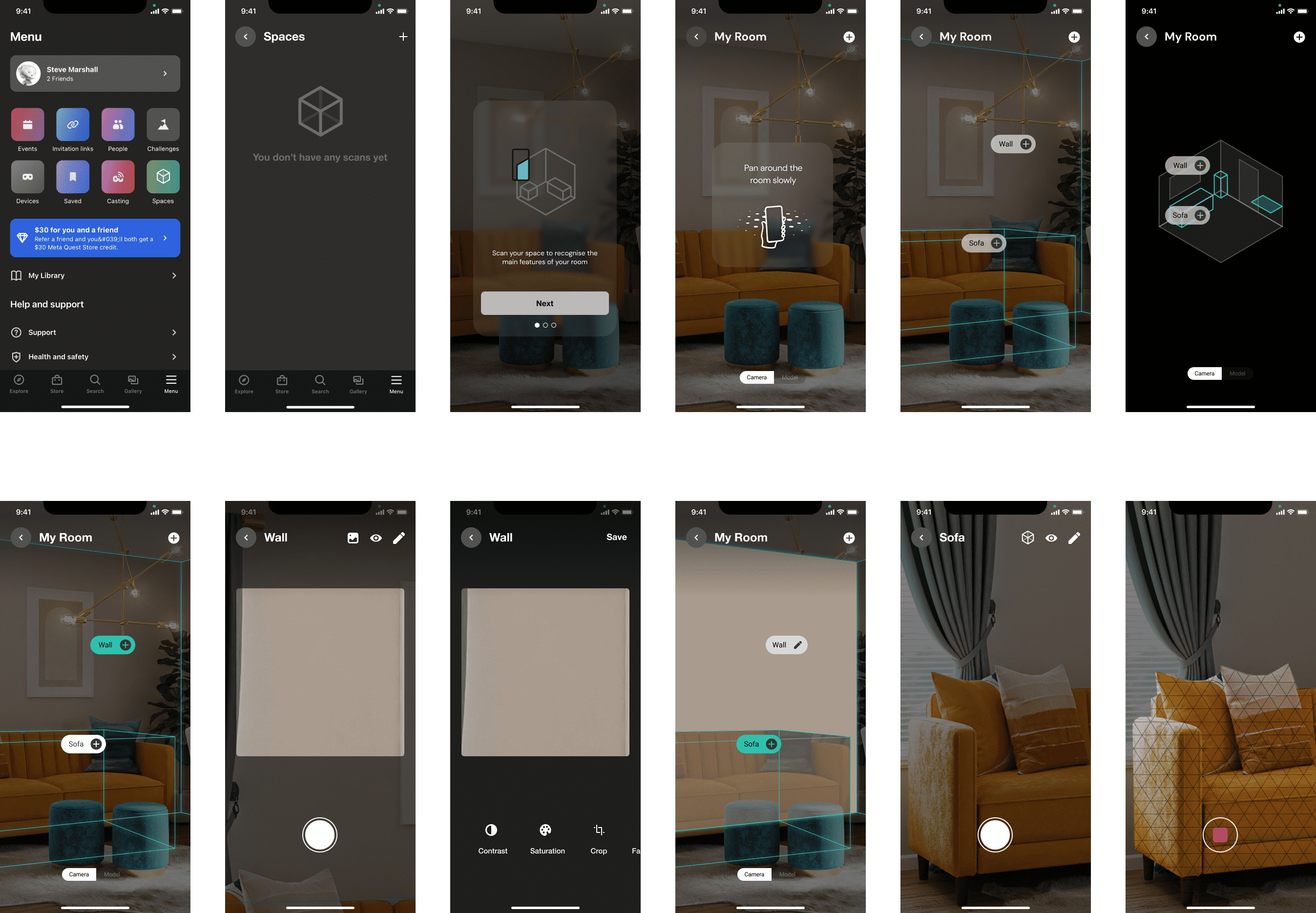

Prototyping the UX

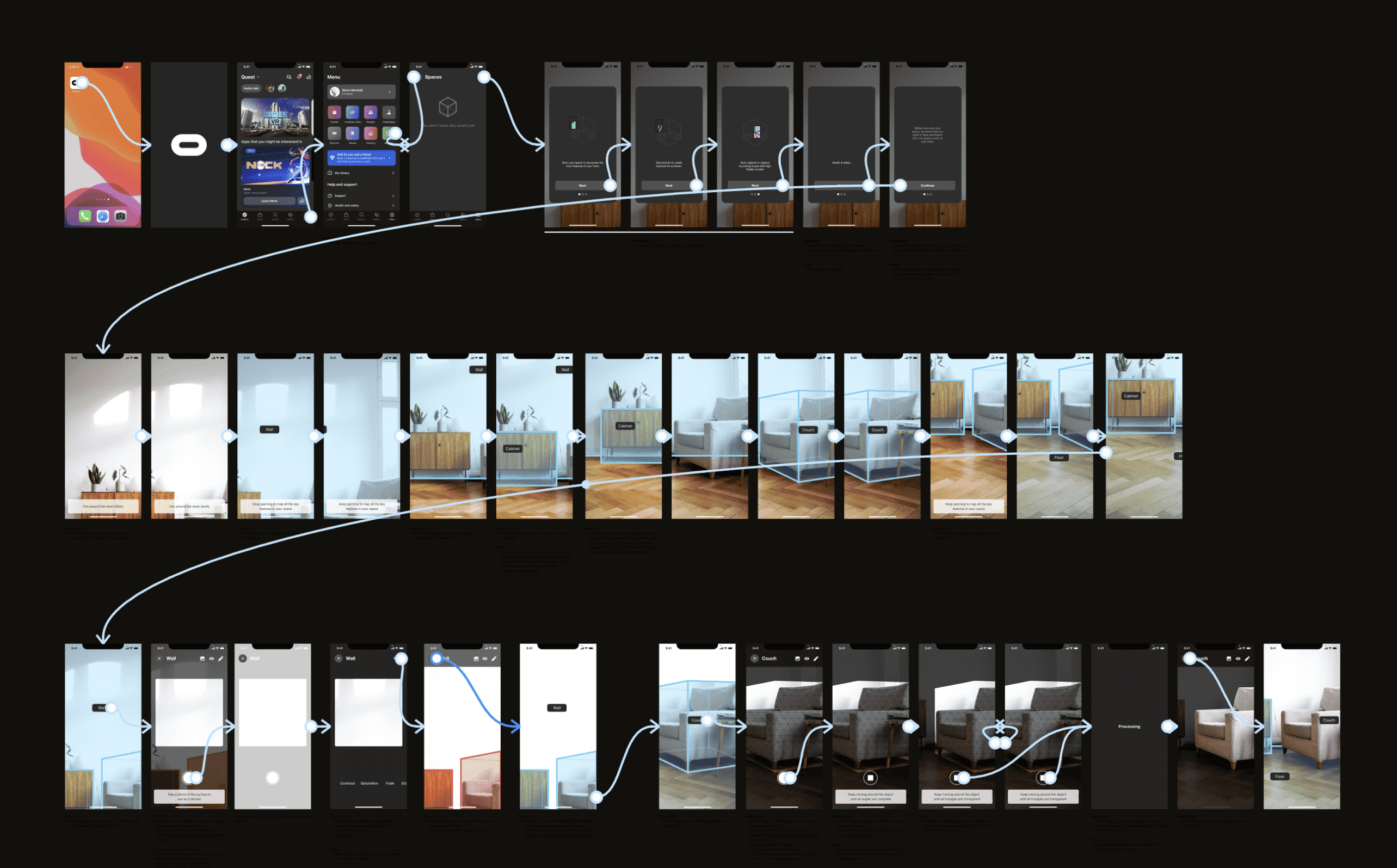

From these requirements, I defined the core components of the capture experience—room layout, object volumes, textures, and meshes—and translated them into high-level flows and Figma prototypes.

A key insight was the need to minimize disruption to VR use. We proposed a non-linear capture process that allowed users to incrementally add fidelity over time:

- Scan for surfaces and object volumes.

- Capture textures to customize spaces.

- Scan individual objects to replace low-fidelity geometry.

This approach allowed users to quickly bring a usable version of their space into VR, then progressively refine it as needed—balancing effort, control, and immersion.